A Boy’s Town

Excerpts from the book By William Dean Howells.

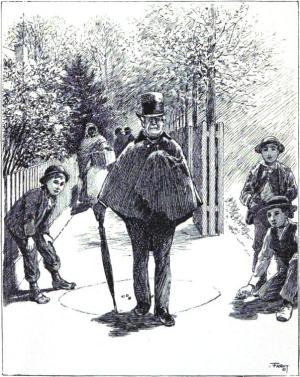

In the Boy's Town they had regular games and plays, which came and went in a

stated order. The first thing in the spring as soon as the frost began to come

out of the ground, they had marbles which they played till the weather began to

be pleasant for the game, and then they left it off. There were some

mean-spirited fellows who played for fun, but any boy who was anything played

for keeps: that is, keeping all the marbles he won. As my boy was skilful at

marbles, he was able to start out in the morning with his toy, or the marble c

.*. he shot with, and a commy, or a brown marble of the lowest value, and come

home at night with a pocketful of white-alleys and blood-alleys, striped

plasters and bull's-eyes, and crystals, clear and clouded. His gambling was not

approved of at home, but it was allowed him because of the hardness of his

heart, I suppose, and because it was not thought well to keep him up too

strictly; and I suspect it would have been useless to forbid his playing for

keeps, though he came to have a bad conscience about it before he gave it up.

There were three kinds of games at marbles which the boys played: one with a

long ring marked out on the ground, and a base some distance off, which you

began to shoot from; another with a round ring, whose line formed the base ; and

another with holes, three or five, hollowed in the earth at equal distances from

each other, which was called knucks. You could play for keeps in all these

games; and in knucks, if you won, you had a shot or shots at the knuckles of the

fellow who lost, and who was obliged to hold them down for you to shoot at.

Fellows who were mean would twitch their knuckles away when they saw your toy

coming, and run; but most of them took their punishment with the savage pluck of

so many little Sioux. As the game began in the raw cold of the earliest spring,

every boy had chapped hands, and nearly every one had the skin worn off the

knuckle of his middle finger from resting it on the ground when he shot. You

could use a knuckle-dabster of fur or cloth to rest your hand on, but it was

considered effeminate, and in the excitement you were apt to forget it, anyway.

Marbles were always very exciting, and were played with a clamor as incessant as

that of a blackbird roost. A great many points were always coming up : whether a

boy took-up, or edged beyond the very place where his toy lay when he shot;

whether he knuckled down, or kept his hand on the ground in shooting; whether,

when another boy's toy drove one marble against another and knocked both out of

the ring, he holloed "Fen doubs!" before the other fellow holloed " Doubs !"

whether a marble was in or out of the ring, and whether the umpire's decision

was just or not. The gambling and the quarrelling went on till the second-bell

rang for school, and began again as soon as the boys could get back to their

rings when school let out. The rings were usually marked on the ground with a

stick, but when there was a great hurry, or there was no stick handy, the side

of a fellow's boot would do, and the hollows for knucks were always bored by

twirling round on your boot-heel. This helped a boy to wear out his boots very

rapidly, but that was what his boots were made for, just as the sidewalks were

made for the boys' marble-rings, and a citizen's character for cleverness or

meanness was fixed by his walking round or over the rings. Cleverness was used

in the